One of the more interesting minor characters of the Old Testament is Eli the Priest. His story can be found in the opening four chapters of the First Book of Samuel (also, confusingly, known as the First Book of Kings). So interesting is he, in fact, that in a rare exception to the normal practice, which I mentioned in a previous post, modern imaginative contemplators will depart from the Gospel to apply themselves to one of the stories featuring him. Namely, the calling of the boy Samuel by God. This can be found in 1 Samuel Chapter 3 and acts as a kind of sandwich filling between the two episodes I propose to look at in this piece. If you want to meditate on it in your own time then I recommend that you incorporate the full story and don’t cut out the dark ending as many moderns do.

However, I digress. My intention here is to briefly outline the (or a) technique for imaginative contemplation and then illustrate it via the stories of ‘Eli and the (Apparent) Drunk’ and ‘Eli and the Dangerous Chair (or Stool)’.

The Technique

First find your object of contemplation. Read the Bible, locate stories that are discrete, preferably vivid, and potentially useful windows into something the Holy Spirit wants to teach us about.

Before beginning to pray form an intention for your prayer. That is, you may be offering your prayers as a petition for world peace and for Baby to sleep all through the night. So that’s your intention.

Bridging prayers. You want to move your mind from the things of the world to those of the spirit and using set prayers is a good way to do that. Traditionally Catholics have said an ‘Our Father’ an ‘Hail Mary’ and an ‘I Believe’ (the Apostles Creed). Since I have never memorised the Apostles Creed I tend to go for a ‘Glory Be’ instead. Don’t sweat the precise details of the format, just make sure that you have one. Since the Second Vatican Council there has been a tendency to sweep away the formal prayers and substitute them with an invitation to ‘put yourself in the presence of God’. Presumably this is because of a suspicion that the traditional approach is over-pious and mechanical. Actually, whatever its spiritual merits the older method is psychologically astute, by having a fixed ritual, which becomes a habit, the mere act of doing it will effect an alteration in your mind’s direction of focus, because your internal auto-pilot will be working on behalf of your change in focus. A conscious effort, new every time will, counter-intuitively perhaps, be less effective.

Read the portion of text you are about to meditate upon. Then read it again but more slowly.

Then imagine the events within it as they unfold and follow them closely with your attention. Some of you can do this cinematically, using your visual imagination, and some of you will find it easier to translate the text into a radio play or an audiobook. The point is that you pay attention, how you do so is secondary, provided that you don’t keep stopping the action to analyse its deeper meaning and significance. Your role is to be an observer, not a participant, not an author, not a commentator, not a teacher. You can, during the exercise, try to perceive this or that part of the story from the perspective of one of the characters-how they feel, what they see, what they hear-but you are not that character, you do not direct their next actions or words.

If you have a good memory you can close your Bible and put it to one side before you begin. If you have a memory like a sieve, especially for dialogue, then it may help to leave it open and near at hand to refer to when you get stuck as to what happens next.

Once you reach the end then offer up thanks and your outward-bound bridging prayers.

Prayer is supposed to make a difference to how you are in the world so making practical resolutions flowing from what you have just prayed about is a practice much recommended by the Saints.

Don’t meditate on the same passage twice in the same day. You can do it several times in a week or in a month. It will probably not be a repetition so much as a deepening and a texturing of your insight into the episode towards which you are being attentive.

Eli and the (Apparent) Drunk

This is right at the beginning of 1 Samuel. The backstory is found in 1 Samuel 1:1-8. We take up the events beginning at verse 9 (in a rare concession to ecumenism I am using the ESV translation)-

After they had eaten and drunk in Shiloh, Hannah rose. Now Eli the priest was sitting on the seat beside the doorpost of the temple of the LORD.

Since I’m not an historian all or many of the details which I am imagining may be wildly wrong as a matter of fact but since they are just the setting within which an eternally valid story is being told I won’t let that worry me.

Hannah is a woman who is desperate to have a child. She is teased and tormented by others because of her childlessness. When we get to verse 18 we see a suggestion that at this point (verse 9) she actually ate and drank very little. Perhaps pushing away her food untasted she arose pale and upset to go into the temple seeking consolation through prayer.

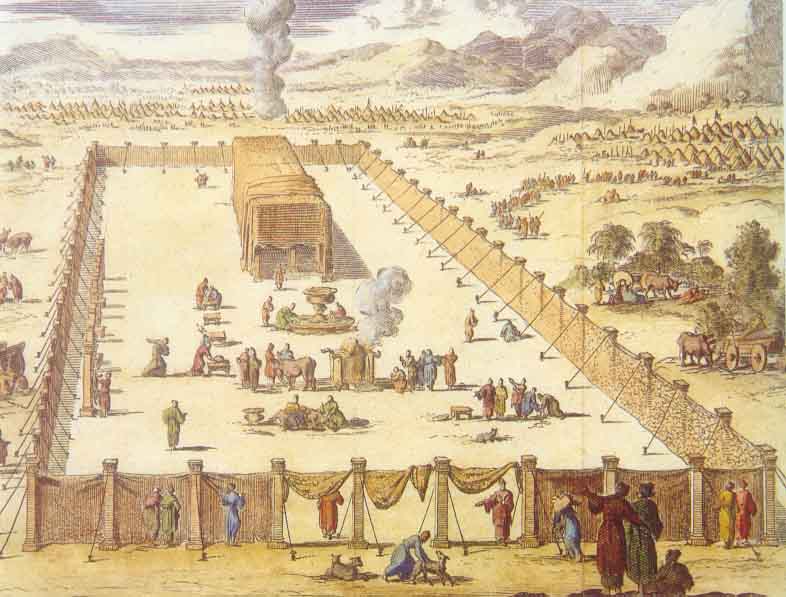

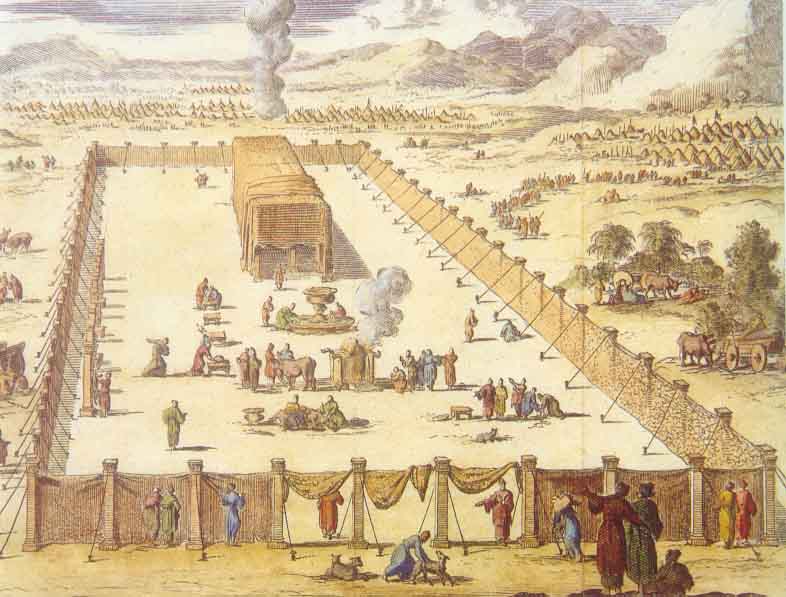

This was not the great stone Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem, that lay far in the future, this was probably more like the tented structure built by Moses for transportation in the wilderness. There would have been a large courtyard within the temporary walls, and within that there would have been another structure where the Ark of the Covenant was kept, the Holy of Holies. So, Hannah was praying in the courtyard and Eli was sitting by the entrance to the Holy Place.

While you may want to fill in the details of the story you are meditating on, try not to get too sidetracked into every little thing. I know a man in Christ who fourteen days ago got snatched up into wondering about the seat of Eli. In the later episode which we are to consider he is sitting somewhere else. Is it the same seat? How portable is it? Are they different seats? Perhaps there are benches set up at strategic locations in the temple complex. The Douay-Rheims translation uses the word ‘stool’ to describe the seat and that fits in well with the events of that later episode. So, I, that is, the man that I know, settled on stool as the best word to describe what Eli was sitting on. Now, was it or was it not upholstered…? This level of detail is somewhat excessive. Avoid it if you can.

Verses 10-11 read-

She was deeply distressed and prayed to the Lord and wept bitterly.

And she vowed a vow and said, “O Lord of hosts, if you will indeed look on the affliction of your servant and remember me and not forget your servant, but will give to your servant a son, then I will give him to the Lord all the days of his life, and no razor shall touch his head.”

Although she may have been pale at the beginning, now her face has become red and distorted by ugly-crying. She is so desperate for a son (and it had to be a boy not a girl, those were the days of actual not imaginary patriarchies) that she promises that as soon as she gets him she will hand him back to God. What she needs to demonstrate is that she is able to accomplish that which is expected of her as a married woman and a daughter of Israel.

The reference to the razor is to the Nazirite vows of a person consecrated to God. During the period of their vow of consecration a person did not cut their hair. When the time was over they did. What Hannah is doing here is making a lifelong vow on behalf of her as yet unconceived son. She would have been secure in the knowledge that when he did turn up he would fulfil the vow since in those far-off times children did what their parents told them to do. I know! Hard to imagine isn’t it?

The next two verses go-

As she continued praying before the Lord, Eli observed her mouth.

Hannah was speaking in her heart; only her lips moved, and her voice was not heard. Therefore Eli took her to be a drunken woman.

Eli would have been looking at a combination of red-faced ugly-crying, lips moving rapidly but silently and the head and body moving convulsively because of Hannah’s passionate intensity and focus on her anguish. So his error was understandable.

And Eli said to her, “How long will you go on being drunk? Put your wine away from you.”

But Hannah answered, “No, my lord, I am a woman troubled in spirit. I have drunk neither wine nor strong drink, but I have been pouring out my soul before the Lord.

Do not regard your servant as a worthless woman, for all along I have been speaking out of my great anxiety and vexation.”

(Verses 14-16)

Recall their location. They were in the courtyard of the temple, just by the entrance to the Most Holy Place and the Ark of God. Recall too that Eli was effectively the head-priest in Israel at this time. So he wasn’t being an officious busybody when rebuking Hannah; if she really had been drunk she would have been disrespecting the sacred space where she was standing.

Hannah then defends herself. She does not say ‘who the hell do you think you are?’ as her 21st century descendants might do. She concedes that Eli has a duty to defend the integrity of the sanctuary of God in Shiloh. What she says is that he has misperceived the situation and that all the symptoms that he saw were signs of her being distraught and laying all her troubles before the Lord God, which was, after all, one of the functions of the temple. Notice though that she does not say what it was that was troubling her. And Eli does not ask her this. What lies between a praying soul and the Lord is privileged, we can share it with others if we wish. But not if we don’t so wish.

Then Eli answered, “Go in peace, and the God of Israel grant your petition that you have made to him.”

(Verse 17)

Although he doesn’t apologise Eli immediately course-corrects. He recognises that Hannah is not drunk. She is a sincere worshipper of the Lord who has turned to Him in her great need. So he adds his petition, as chief priest, to hers even though he does not know what it is, showing her that he has great confidence in her judgement, that what she is asking for must be good and right.

And she said, “Let your servant find favour in your eyes.” Then the woman went on her way and ate, and her face was no longer sad.

(Verse 18)

Prayer, sympathy, and solidarity combined with strong faith have had a healing effect on Hannah. Unless the incident extended over a very long time we must assume that it also restored her appetite. After returning to the family tent she tucked into the leftovers from lunch and looked bright and uplifted. Hopefully, so do you after this exercise in imaginative contemplation. Don’t forget to make your resolutions now.

Eli and the Dangerous Chair (or Stool)

This episode is to be found in 1 Samuel 4. There is lots of backstory here but before we get to the object of contemplation proper the author kindly does a TL;DR for us-

So the Philistines fought, and Israel was defeated, and they fled, every man to his home. And there was a very great slaughter, for there fell of Israel thirty thousand foot soldiers.

And the ark of God was captured, and the two sons of Eli, Hophni and Phinehas, died.

(1 Samuel 4:10-11)

Then we come to verse 12-

A man of Benjamin ran from the battle line and came to Shiloh the same day, with his clothes torn and with dirt on his head.

Now, the author isn’t telling us that the Benjaminite was a scruffy ragamuffin. Rending your clothes and putting dust on your head was a stylised form of mourning. It was a normative sign of grief in that region for centuries so we can suppose that there was a particular method of doing it which meant that anyone seeing a person thus disfigured would know that something bad had happened.

Moreover it may be that the man in question wasn’t just a random soldier who fled from the scene and headed towards the town where the religious cult of Israel happened to be centred. Possibly he was regularly employed as a messenger and that he was acting as a courier. Which, again, may have meant that there was something about him which enabled people to recognise his function, so that as soon as they saw him they knew he was bringing important dispatches, and not good ones either.

When he arrived, Eli was sitting on his seat by the road watching, for his heart trembled for the ark of God. And when the man came into the city and told the news, all the city cried out.

(Verse 13)

So, it would seem that Shiloh consisted of at least two parts, the temple complex and the ‘city’ which was probably actually quite a small town by modern standards. The runner went first to the city leaving Eli anxiously sitting on his seat (or stool) waiting for news. At this point hold in your mind the fact that it wasn’t his sons, who had gone out to the war zone, that most acutely concerned him. It was the Ark.

The part of an Israelite town where all public business was transacted (and where all the gossips gathered) was ‘the gate’. One of the entrance places to the city was a natural place for travellers to stop and pass on their news, sell their goods, and take a rest. And, since the locals were gathered there for such purposes anyway they might as well transact all their own business, commercial and familial in the same space. So, if the messenger arrived there first he would have maximum impact. He only had to tell his story once and it would be all over the town like a rash before he could say Jack Robinson eighty-six times.

Verse 14 tells us-

When Eli heard the sound of the outcry, he said, “What is this uproar?” Then the man hurried and came and told Eli.

But telling the town wasn’t the same as telling the temple. Now, presumably Eli was not alone. Perhaps he had a younger assistant at his side (someone who could carry his stool for him from the courtyard to the main entrance). So the assistant was dispatched to find out the cause of the noise. He came and found the messenger who, despite being tired from his already long run, hastened, out of respect for the priesthood, to tell Eli all the news.

Now Eli was ninety-eight years old and his eyes were set so that he could not see.

(Verse 15)

While his assistant was away fetching the Benjaminite Eli was alone. He was in a world of darkness because of his blindness. He was trembling with worry about the Ark. He had heard an outcry from the town. Now, distressed and grief-stricken crowd noises sound different from joyful ones. But at this distance could he be sure he had interpreted them aright? He waited and his stress levels would have kept rising. Not good for a ninety-eight year old. Especially if he’s sitting on a dangerous chair.

And the man said to Eli, “I am he who has come from the battle; I fled from the battle today.” And he said, “How did it go, my son?”

(Verse 16)

One indication that the messenger may have been a professional at the job was the subtle way that he told his story. This will not be obvious when we read the whole thing in three seconds flat. Note, though, as we progress through it how each statement builds on that of its predecessor. Also, without wishing in any way to be stereotypical, people in the Middle East are not famed for the way in which they react to events with a stiff upper-lip and a strong sense of quiet restraint. It may be that the courier’s report was punctuated by a certain amount of vocally expressed lamentation, which would have made it last longer in real life than it appears to do on the page.

Be that as it may. In his opening remarks he tells Eli where he has been-the battlefield-and what he has done-fled from it. This prepares the priest to hear bad news without actually referring explicitly to it.

He who brought the news answered and said, “Israel has fled before the Philistines, and there has also been a great defeat among the people. Your two sons also, Hophni and Phinehas, are dead, and the ark of God has been captured.”

(Verse 17)

This is where we get to the carefully thought-through sequencing. First: we lost a battle. Secondly: we didn’t just lose, we got totally smashed into smithereens. Thirdly: your two boys have been killed by their enemies (which would also carry the implication that they would not receive a decent burial. A big consideration in those days). And fourthly, the Ark of the Covenant is in the hands of the deadliest enemies of God and of the people of Israel. That the high priest should be more concerned about the Ark than about his own two sons is taken for granted both by the author of the Book of Samuel and by the Benjaminite. And rightly so as the very next verse demonstrates.

As soon as he mentioned the ark of God, Eli fell over backwards from his seat by the side of the gate, and his neck was broken and he died, for the man was old and heavy. He had judged Israel for forty years.

(Verse 18)

It will be thought by some, or at least by one, that the most important thing that this demonstrates is that Eli was sitting on a backless chair. Which means that it was probably a stool. But that is not, in fact, the most important thing. It is that the priest of God shared in the assessment of the messenger that the most vitally important item of news was, despite the nationally and personally devastating aspects of the other events, the capture of the Ark. This is especially significant if you know from the backstory that Eli had some reason to be humanly resentful against the Lord.

What sort of feeling did the characters in this story have for the Ark? Well, Christians see in either Mary or Jesus or both the new Ark of the Covenant by which they mean that the place where we find Emmanuel, God-with-us is in the womb of Mary, in the person of Mary’s Son. For the Israelites the Ark was their Emmanuel, their dearest love, their fondest hope, the pledge of the Covenant with God. Its seizure by the enemy posed an existential threat to the people. If it was gone, had the Almighty gone? Had He repudiated the Covenant? Were they about to be destroyed as a nation and eliminated from history? The Ark really, really, really mattered to them.

So Eli, being old, and brittle-boned, and heavy, and highly stressed fell, perhaps he also had a stroke, and broke his neck and died. There is a sad appendix to this story over the next three verses which tells of the story of his heavily pregnant daughter-in-law. But if you wish to add that to your contemplating you will have to do your own imagining. For my part; that’s all folks.

The picture, which represents the Tabernacle in the wilderness, comes from the My Jewish Learning website.